Multi-Container Pod Design Patterns in Kubernetes

Multi-container pods are extremely useful for specific purposes in Kubernetes. While it’s not always necessary to combine multiple containers into a single pod, knowing the right patterns to adopt creates more robust Kubernetes deployments.

Last updated 9 June, 2018. Contact me to report inaccuracies.

Get my book Golden Guide to Kubernetes Application Development. If you’re a web application developer who wants to become a Kubernetes expert very quickly, check out the book.

The Multi-Pod Lifestyle

Pods will often only have one container—this is OK. One of the downsides of having a pod as an extra layer of abstraction around a container is that it seems like you should have multiple containers for a pod to be useful.

In fact, the opposite is true: single-container pods are more often the correct answer. Kubernetes adds "pods" so that you can have different types of containers—Docker, rkt, etc—managed by a single orchestration system. It also allows pod-level control of restart policies, networking, and filesystem sharing.

You don't always need to use multi-container pods. When should you combine multiple containers into a single pod?

When the containers have the exact same lifecycle, or when the containers must run on the same node. The most common scenario is that you have a helper process that needs to be located and managed on the same node as the primary container.

Another reason to combine containers into a single pod is fro simpler communication between containers in the pod. These containers can communicate through shared volumes (writing to a shared file or directory) and through inter-process communication (semaphores or shared memory).

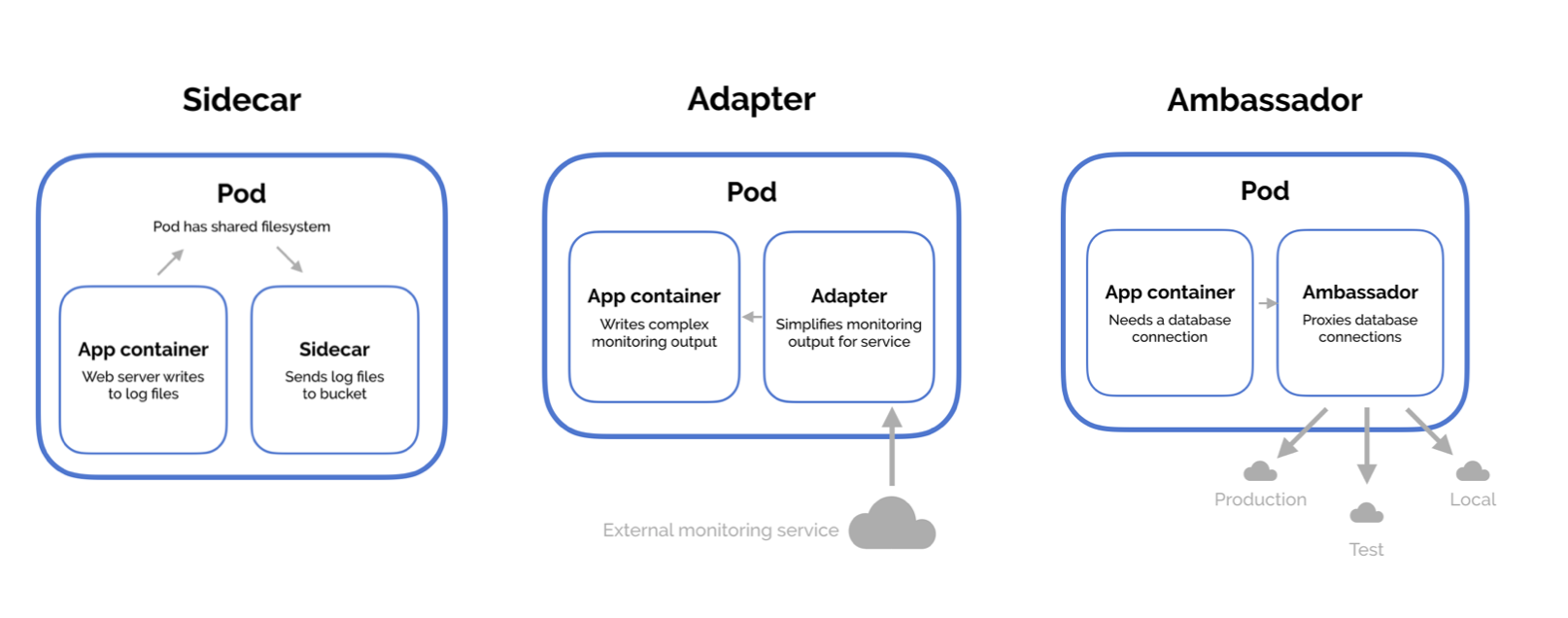

There are three common design patterns and use-cases for combining multiple containers into a single pod. We’ll walk through the sidecar pattern, the adapter pattern, and the ambassador pattern. Look to the end of the post for example YAML files for each of these.

Sidecar pattern

The sidecar pattern consists of a main application—i.e. your web application—plus a helper container with a responsibility that is essential to your application, but is not necessarily part of the application itself.

The most common sidecar containers are logging utilities, sync services, watchers, and monitoring agents. It wouldn't make sense for a logging container to run while the application itself isn't running, so we create a pod that has the main application and the sidecar container. Another benefit of moving the logging work is that if the logging code is faulty, the fault will be isolated to that container—an exception thrown in the nonessential logging code won't bring down the main application.

Click here for an example pod using the sidecar pattern for log management

Adapter pattern

The adapter pattern is used to standardize and normalize application output or monitoring data for aggregation.

As a simple example, we have a cluster-level monitoring agent that tracks response times. Say we have a Ruby application in our cluster that writes request timing in the format [DATE] - [HOST] - [DURATION], while another Node.js application writes the same information in [HOST] - [START_DATE] - [END_DATE].

The monitoring agent can only accept output in the format [RUBY|NODE] - [HOST] - [DATE] - [DURATION]. We could force the applications to write output in the format we need, but that burdens the application developer, and there might be other things depending on this format. The better alternative is to provide adapter containers that adjust the output into the desired format. Then the application developer can simply update the pod definition to add the adapter container and they get this monitoring for free.

Ambassador pattern

The ambassador pattern is a useful way to connect containers with the outside world. An ambassador container is essentially a proxy that allows other containers to connect to a port on localhost while the ambassador container can proxy these connections to different environments depending on the cluster's needs.

One of the best use-cases for the ambassador pattern is for providing access to a database. When developing locally, you probably want to use your local database, while your test and production deployments want different databases again.

Managing which database you connect to could be done through environment variables, but will mean your application changes connection URLs depending on the environment. A better solution is for the application to always connect to localhost, and let the responsibility of mapping this connecting to the right database fall to an ambassador container. Alternatively, the ambassador could be sending requests to different shards of the database—the application itself doesn't need to worry.

Examples

Sidecar pattern example

Adapter pattern example

Ambassador pattern example

This example is not easily contained in a Gist, though I’m happy to share it. Get in touch.